Category: Worldviews

Renewable energy, cornucopian dreaming and ‘anti-capitalism’

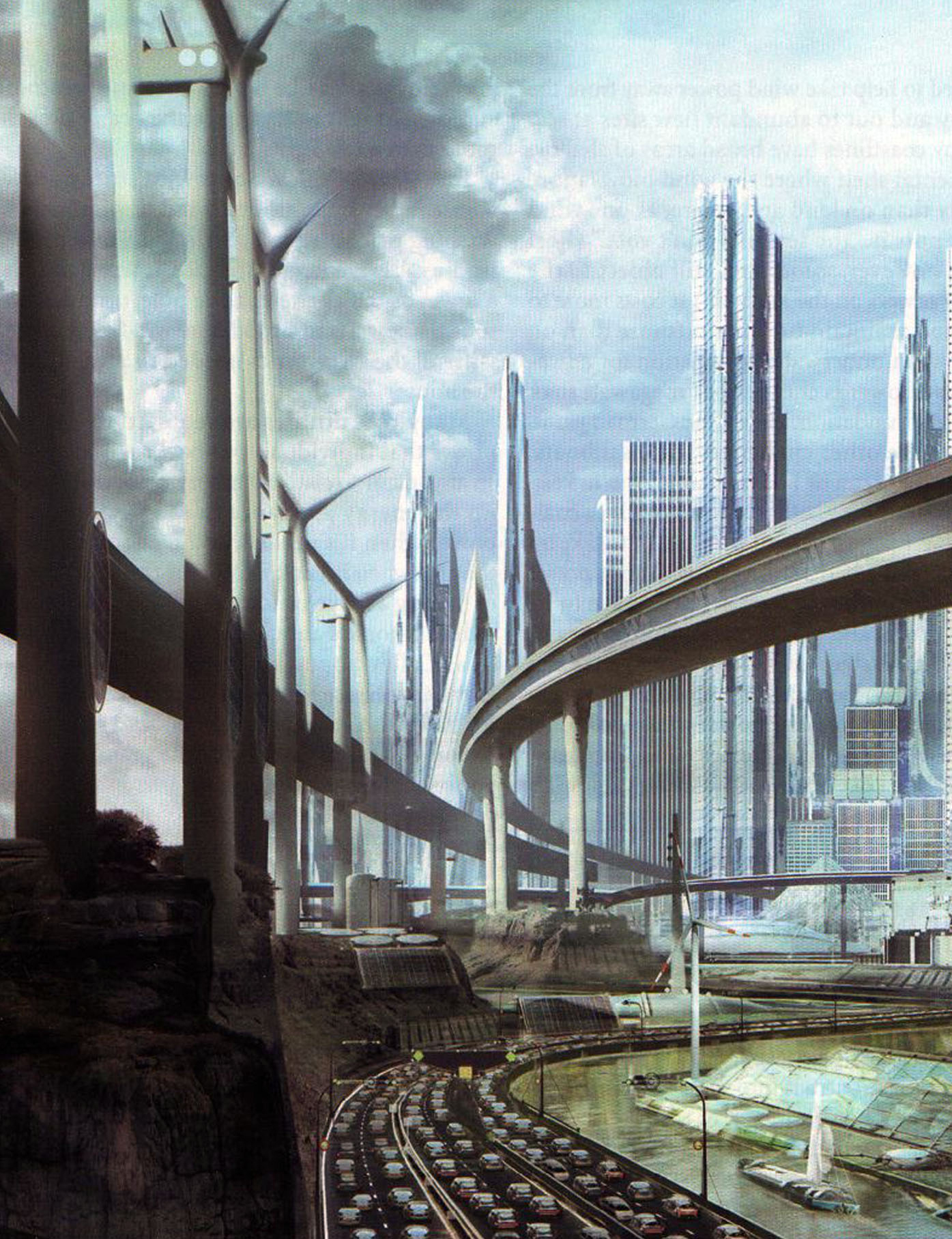

(The above image is from a feature on renewable energy in the ‘National Geographic’ magazine)

These notes cover a range of topics raised in a debate on Facebook (March 2020: https://www.facebook.com/sandy.irvine.18/posts/1344237949096381 ). It was triggered by an article by Bill Rees (https://thetyee.ca/Analysis/2019/11/11/Climate-Change-Realist-Face-Facts/?fbclid=IwAR3ggTgf-Urra0SE9OhNIXTdPkua4R3QuQYBGPdrfaStWLuniv-NEMAEiZ8).

Part of the debate was the intrinsic limitations of renewable energy technologies (regardless of their desirability on other grounds) and the wider issue of what a sustainable society might be like. However, part of the exchanges extended to calls for the “abolition of capitalism” and the issue of ‘reform’ v ‘revolution’. One contributor to the exchanges called for a planned economy and international ‘state control’.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

As a starting point, we collectively need to keep reminding ourselves of the fundamental reality of limits to growth as well as the extent of current ‘overshoot’ and the corresponding need for substantial degrowth in many sectors, not just obvious ones such as arms production. Specifically, Bill Rees is quite right to argue that ‘renewable energy’ could not sustainably power anything like current society, with its high (and still growing) population levels and high (and still growing) expectations in terms of physical per capita consumption.

As Rees explains, renewables are limited by their low power density and intermittency, while energy storage will also be limited in its capacities. To be sure there have been and, as seems likely, will continue to be improvements in efficiencies etc but there is not energy cornucopia awaiting us. This is a case backed up by many studies eg https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/09/06/the-path-to-clean-energy-will-be-very-dirty-climate-change-renewables/. A particularly interesting paper is this one from Australia: http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue87/TrainerAlexander87.pdf. It also looks at lifestyle implications, something avoided by those who glibly demand “system change” but do not explore what in detail that would mean in terms of diet, clothing, shelter, and so much more.

We do not, of course, live by energy supply alone but need land and water for many other things as well. That finite space is also needed by a myriad of other species for habitat (the scale of that latter requirement in terms of biodiversity conservation is suggested here: https://www.half-earthproject.org ). There are, then, unavoidable trade-offs between competing uses for what is a finite amount of physical space. In any case, only some of that land, river and sea is suitable for renewable energy devices such as wind turbines, thereby intensifying that inherent geophysical limitation. Abstract aggregations of theoretically possible output tell us little about those trade-offs and opportunity costs.

There are also side-effects of some renewable energy technologies such as the terrible impact of neodymium production (for magnets) that are also ignored. To date, the impact of large HEP dams has arguably been more destructive than that of the radioactive white elephant of nuclear power. Both local human communities and critical wildlife habitat have been destroyed by HEP schemes, which, in warmer parts of the world, also generate significant volumes of greenhouse gases (eg https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2016/nov/06/hydropower-hydroelectricity-methane-clean-climate-change-study) Large-scale biomass energy is another ruinous energy source, requiring vast chemically saturated monoculture to produce significant yields. It literally takes food out of the mouth of people and instead ‘feeds’ vehicles.

We have to look beyond carbon emissions and consider not just all greenhouse gases but also the sheer depth and breadth of the various ecological crises we face, from soil erosion and aquifer depletion to coming peaks in certain specific resources such as phosphorus and some rare earths. There is little to be gained ‘solving’ the energy crisis by making those other crises worse. Indeed, abundant energy probably would speed up the rate at which forests are being felled, wetlands drained, farmland overtilled, roads filled with vehicles and so on. The ‘rebound effect’ might also cancel out some gains in energy efficiency (to which there are ceilings anyway).

On a more specific point, it is very ungreen thinking to perceive deserts as just wasteland, there to be exploited (cf https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/habitats/deserts/; see also the work of Gary Nabhan in particular eg https://uapress.arizona.edu/book/gathering-the-desert ). There are several critical studies of the dream that, say, the Saharan desert could power Europe with gigantic solar collectors and a gigantic grid, eg http://www.greens.org/s-r/60/60-09.html . It might be noted that dependence on solar energy from lands potentially ruled by the likes of Colonel Gaddafi might be as unwise as that on oil from the Middle East. [On the politics of the Sahara region, see, for example: https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/crisis-watch-2020-sahel-24705 ]. In any case, desert solar power towers are not unproblematic eg https://eu.desertsun.com/story/tech/science/energy/2016/08/17/how-many-birds-killed-solar-farms/88868372/

Of course, many attack the notion of degrowth to a steady-state economy as some kind of ‘miserabilism’, probably needing a Mao-style dictatorship. Let us be clear, then, it is quite possible to combine the necessary degrowth with a stable, convivial, much fairer and democratic society. On many fronts, from personal health to a reconstruction of local community bonds, there is much to be gained. Indeed, there is much empirical evidence eg http://www.fodorandassociates.com/book/bnb_info.htm . Organisations such as Simplicity Institute (Australia) and Post Carbon Institute (USA)have also compiled a compelling evidence base. Renewables could supply enough energy for civilised living providing we keep human numbers in check. Indeed, Bill Rees point out that the USA of 50 years ago managed reasonably well on far less energy. I once spent a few days in Amish country. People there seemed healthy and happy but used far less energy than their neighbours. The key point is that ‘mass consumerism’ and renewables cannot go together. The community on Eigg gives an idea of what a renewable energy budget might power (https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20170329-the-extraordinary-electricity-of-the-scottish-island-of-eigg) and, to be honest, it does depend on a fair bit of tourist income (ie on people who have travelled there courtesy of fossil fuels).

But, to explore the transitional steps to get from here to there, we need to drop empty revolutionary rhetoric. The notion that all our problems could be solved by the “abolition of capitalism’ is simplistic, to say the least. Many anti-capitalists do not even agree on what actually is ‘capitalism’ (just look at the tiny Trotskyist movement to sample how definitions vary even in such small circles) so it is far from clear what is to be abolished. In any case, there are huge between countries and, within them, between provinces and councils at a policy level. It underlines how crude it is to think that there is one ‘system’ that dictates that things will be one way and no other.

Furthermore, it is false to pose ‘market tools’ versus ‘state control’. There is a place for both. As the fast and large-scale reduction in plastic bag usage shows, the price mechanism can sometimes work very well. In 1921, the ‘market; saved many Russians from starvation.

But we need to judge things on a case by case basis. As the ‘neo-Trotskyist’ theorist Tony Cliff argued, the distinctive nature of agriculture, as opposed to manufacturing, means that “the private farm (will have) a new lease of life under the socialist regime.” There is a case for public ownership of inherent ‘unities’ but many other economic activities could be conducted by other organisations, ranging from (regulated) for-profit enterprises to ‘benefits corporations’, producer and consumer cooperatives, land trusts and community banks. Often, the size of the enterprise, not its ownership, will be the critical parameter. We need in-depth debate about the best combinations, not empty sloganeering.

Demands to abolish capitalism actually leave begging all the key questions. How big would the overall economy be? What size of population would be sustainable, locally as well as nationally and globally? What levels of per capita consumption are durable? What technologies would it use and what ones would it reject? We cannot put off such questions until ‘after the revolution’ (a rather unlikely event in any case). All the evidence suggests that the only sustainable option is to ‘think shrink’ and the bigger the current economy the deeper the shrinkage will have to be if we are to avoid collective ruination (https://www.overshootday.org/newsroom/country-overshoot-days/)

Substituting planned production for social use for private production for profit makes no difference in itself in terms of sustainability. Ambulances made in a state enterprise have the same ecological costs as armoured cars made in a private firm, regardless of their different social value. Nuclear power plants will still need uranium mines and dump radioactive waste on future generations, regardless of social control and usage.

In any case, the historical record of centralised planning is not a good one, as dissident economists in the Soviet Bloc such as Oscar Lange came to recognise. Indeed, the worst environmental and humanitarian disasters of the 20th century happened in planned economies, ones comparatively insulated from the world market (see, for example: http://www.frankdikotter.com )

‘International state control’ could be a bureaucratic nightmare and likely to degenerate an inefficient, unbending and unresponsive (http://duaneelgin.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/the_limits_to_complexity.pdf) What we actually need is radical decentralisation, ideally along bioregional lines, with each local economy and society adapted to the patterns, capacities and limits of their ‘ecoregion’ (see: https://sandyirvineblog.wordpress.com/2017/11/28/regionalism-devolution-and-subsidiarity/

The posing of a reform v revolution dichotomy is false anyway. We need a transitional programme, with a myriad of changes, some big, others seemingly small but still significant in terms of cumulative impact. Berne Sanders, for example, is no revolutionary but a reformist. That does not mean he has no good ideas and ones that are quite practicable in the here and now (https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/110915/review-bernie-sanders-economic-policies.asp ). Clement Attlee specifically denied being a socialist but his government did some very good things in what were very discouraging circumstances.

What the ‘Hard Left’ routinely dismisses as ‘reformism’ has delivered major improvements in the lives of ordinary people. The NHS as well as , before it, national insurance and pensions legislation reduced a lot of poverty, insecurity and sickness. Public housing took a lot of people out of slums as did private reformist initiatives such as Quaker ‘model village’ projects (Bournville etc). Accumulated health and safety legislation might not go far enough but we are better off with it than without it. Children benefited enormously from reforms on child labour. Much as I loathe Tony Blair, his government’s ‘Sure Start’ programme did help a lot of youngsters and their parents.

There are also plenty of examples of beneficial environmental reforms. Controls over CFCs for example, saved many people from skin cancer and worse. Sanitation reforms delivered huge public health benefits. Town and country planning did protect some beautiful environments while access legislations opened new recreational opportunities for ordinary people. A lot of successive reforms can, of course, create a huge overall change in the nature and functioning of society eg https://steadystate.org/discover/policies/

Now let us consider ‘revolution’ (in the sense of a dramatic ‘big bang’ transformation). I’ve just tried to skip through Wikipedia’s very long list of revolutions. What struck me was how many of the ‘successful’ ones led to dire consequences, often the opposite of the original goals of their leaders. Indeed, revolutions regularly do ‘eat’ both their children and their parents. A dynamic of escalating violence has routinely been present. By far the most numerous victims of the French Revolution, for example, were poor people, many of them children (eg the ‘noyades”). Even less bloodthirsty revolutions could threaten ‘innocent’ groups eg the bad consequences of the then newly independent USA, post-revolution, for both native Americans and slaves).

Indeed, the speed of degeneration across many revolutionary regimes surprised me. Thus, after only a few weeks of being in power, the Bolshevik regime created a secret police organisation, the Cheka, to suppress striking workers, ie well before the ‘White’ counter-revolution. Even the remarkable Haitian revolution involved some terrible crimes, including the massacres of mulattos. There was indiscriminate violence on all sides. Revolutions do, then, seem to have a way of brutalising those that made them

At the very least, it might pay to be more circumspect in calls for the revolutionary overthrow of this, that and the other. We need ‘wins’ in the here and now otherwise there will be little left to save. But we also need a realistic vision of what a sustainable society might be like. To return to the original post, it won’t resemble the imaginings of assorted cornucopians, be they ‘Left’ and ‘Right’.

Scientism and its dangers

This is an interesting article that touches on the dangers of ‘scientism’, of hype about what science is telling us and is able to tell us. Mainstream science is often harmfully embedded in the institutions of the status quo and the cultural ‘mindset’ of our era. It is not some totally ‘objective’ practice and that too can have its dangers as the ‘dispassionate’ scientists who worked on Nazi programmes showed us.

http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/…/dear-skeptics-bash-…/…

This is worth reading too:

http://authors.library.caltech.edu/62179/1/20024542.pdf

Science can, of course, tell us a great deal about the ‘how’. But we need other insights to know the ‘why’, about the ethical ‘ends’ we ought to pursue by those ‘means’.

You must be logged in to post a comment.