Russian drama series about Trotsky on Netflix

Fake news has a very close cousin: fake history. Masters of both are the Russian media under the rule of the ruthless kleptocracy headed by Vladimir Putin. Russian television marked the 100th anniversary of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution with a glossy 8-part serial ‘Trotsky’, made by the production company Sreda. First shown on the country’s premier TV channel, it is now available on Netflix (the team behind the production will simply be called Sreda).

The series is well acted and its action scenes are effectively mounted. If nothing else, it moves along at a fair pace, covering a lot of ground between Trotsky’s political youth and final hours. But, politically, it is most remarkable for its distortion of Trotsky’s life and times. Indeed, it is so bad at times that is perversely compelling viewing: some terrible movies have, of course, become cult films. I could not help watching all of it, given a lifelong interest in the history of the Russian revolution in particular.[i] To be fair, many people probably will learn something from the series. I for one was only vaguely aware, for example, of the ‘Schastny’ affair in which Trotsky does indeed seem to have played a reprehensible role.[ii]

The events of 1917 have an enduring fascination, not least because it was one of those rare occasions when a long established regime was well and truly uprooted, replaced by one radically different. Though society and technology today are very different, there are political lessons to be learned from the advent of Bolshevik rule, not least about what went so very badly wrong afterwards. Indeed, debate about the degeneration of the Russian Revolution may well run, run and run. Thus, it is still debated whether the Bolshevik Revolution was a genuine mass uprising or a putsch (or, perhaps, a mixture of the two). All sorts of questions, from the validity of ‘revolutionary’ politics and of highly centralised ‘vanguard’ parties to tolerance of dissent and the use of political violence, are posed.

The narrative of the whole series is structured around a series of flashbacks, moving forward in time, during a series of interviews late in his life Trotsky is portrayed as having with Frank Jacson (alias of Stalinist agent Ramón Mercader, the assassin of Trotsky in August 1940). Such lengthy exchanges never took place. Quite incredibly, Jacson is portrayed as a young idealist who, even more amazingly, openly supports Stalin in his conversations with Trotsky. At one point, Sreda’s Jacson is shown at one point to be so nice he cannot even kill a rabbit whereas Trotsky merrily bashes it on the head. In reality, Jacson had deviously wormed his way into Trotsky’s circle in his then Mexico City household. in order to murder the former Bolshevik leader on NKVD (and Stalin’s) instructions.

The main linking motifs between the various episodes in Trotsky’s life are a collage of events (mainly of death and destruction) and the military train Trotsky used to travel between fronts in the Russian Civil War. The latter becomes a fearsome monster in its own right, billowing smoke. It is often seen from below as it hurtles past, carrying its ‘angel of death’ on his way to administer more executions, including the decimation of Bolshevik units[iii] and, in one scene, a massacre of innocent peasants.

On top of these is a series of hallucinations in which Trotsky thinks he is being confronted by people from his past. These episodes are mainly used to underline Trotsky’s guilt, his vulnerability and, now and again, his remorse. Perhaps they are also meant to point to someone losing his mind and even wishing his own demise. In the final scene, Trotsky is indeed shown provoking Jacson who almost then acts in self-defence, contradicting all known facts.[iv]

Sreda apparently chose to depict Trotsky as some sort of rock and roll star.[v] It is a choice that instantly dumbs down the subject matter. Indeed, ‘Trotsky’ looks like some sort of over-egged mix of rock biopic/rock opera such as ‘Rocketman’ and ‘Tommy’, into which ingredients from older crime thrillers, such as the gangster’s ‘moll’, have been stirred.

The series received a right royal rubbishing on websites linked to the modern day Trotskyist movement. Clearly, its adherents will tolerate no negative criticism of the “Old Man”. Sreda have indeed bent the stick too far one way. Yet Trotsky and Trotskyism have several shortcomings, some of which, albeit in a crudely ham-fisted way, Sreda spotlights.

Monsters on the rampage

Trotsky is depicted as quite some monster: a psychotically egotistical, utterly amoral, merciless, sex-mad megalomaniac whose sole motivation is personal ambition. Everything is grist to what is portrayed as his murderous mill. Not only is he a bad man to have in charge, he is also a bad husband and parent. He shamelessly betrays his two wives. This brute would even sacrifice his own children, at one point using his son to provide a shield from a would-be assassin.[vi]. At one point, his children shut the door in his face for neglecting them.

Frequently, Trotsky is shown spouting forth about freedom and justice but, for him according to Sreda’s representation, the toiling masses are just sad dupes, there to be used. We see a long list of people sacrificed by Trotsky. His Messiah complex is apparently such that, having taken power in Russia, he seemingly gives it away to Lenin such is his belief in his mission to liberate the entire world. His ruthlessness is such that he will break any number of eggs to make his ‘omelette’. According to Sreda, he is largely responsible for the stinking mess that was thereby cooked. The character of Jacson points out that Stalin only did what Trotsky would have done, an argument that reduces their differences to one of mere personality antipathy (in which case, the question is begged why several veteran Bolsheviks bothered to sign the ‘Platform of the Left Opposition’)[vii]

Fawning women apart, this ‘rock star’ actually has only one real ‘fan’, a drunken sailor with puppy dog devotion. This portrait too is a travesty of the real-life Nikolai Markin, one of the unsung heroes of the Russia Revolution and someone warmly praised in Trotsky himself in his own memoirs.[viii] We first meet him extorting money from a Jewish pawn broker. It is less than clear why someone depicted as a violent anti-Semitic should ‘fall’ for Trotsky, a Jew. Rather predictably, Markin is also depicted as falling for Trotsky’s wife as well, for which act a wrathful Trotsky, elsewhere shown in the series to be an exponent of free love, sends Markin to his death during the Civil War.

In the narrative, Trotsky’s wicked qualities are vouched for by none other than Sigmund Freud. I cannot find any solid references to their meeting but Sreda conjures a head-to-head meeting at a lecture Freud is giving. ‘Smart Alec’ Trotsky points out the flaws in Freud’s argument but this is merely a device to allow Freud to deliver a quick diagnosis (just standing on a staircase for a few moments) of Trotsky’s ruthless lust for power and lack of any mercy (apparently Freud could tell by just watching Trotsky’s eyes: no need for lengthy diagnoses on a psychiatrist’s couch!).

Where Sreda is on stronger ground is Trotsky’s streak of personal vanity and intellectual arrogance. In his history of the Revolution, ‘Ten Days that Shook the World’, John Reed does write of Trotsky’s “pale, cruel face” when, in his most famous speech at the October Congress of Soviets, he verbally consigned protesting Menshevik delegates to the “dustbin of history”. At the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk negotiations in 1918, Trotsky’s haughtiness was commented upon by a number of those present.

Trotsky does seem to have rubbed up the wrong way people who might otherwise have supported him. Lenin’s last testament, for example talked of his “too far-reaching self-confidence”[ix] Trotsky was also viewed as a ‘Johnny-Come-Lately’ by some veteran Bolsheviks, something Stalin skilfully exploited. Arguably Trotsky’s conceit blinded him to the threat posed by Stalin and other opponents.

Later in life, Trotsky continued to behave in the same counter-productive way, dismissing groups that, basically, were on the same side, notably POUM in Spain (the crime of ‘centrism’ being a recurrent term of abuse). The Trotskyist movement was to be similarly warped by a tendency for rancorous hair-splitting and enfeebling splits, political DNA arguably inherited from Trotsky himself.

Villain of the piece

All through the series, Trotsky is shown committing foul deeds. Thus, he is portrayed as the prime culprit behind the execution of the imprisoned Tsar and his family. In reality, he played no part. The Ural Regional Soviet took the initial decision. At roughly the same time, Lenin and just 6 other members of the Central Committee back in Moscow also decided that the act was necessary (to stop the Tsar being released by White armies and becoming a unifying point for anti-Bolshevik forces). It is true that, later, Trotsky did excuse the brutal murder of the Tsar’s family but that does not mean he was behind the deeds. Perhaps Sreda might have paid attention to surviving Romanovs who blame Lenin, not Trotsky, for what happened to their forebears.

He certainly did harsh things to win the Civil War yet his measures were not very different to some of the those employed by Abraham Lincoln to shore up Union troops during the American Civil War — war is a cruel taskmaster. It is worth remembering the view of William Graves, American general and commander of US troops in Siberia at the time: “I am well on the side of safety when I say that the anti-Bolsheviks killed one hundred people in Eastern Siberia, to every one killed by the Bolsheviks”. White general Anton Denikin in particular perpetrated many pogroms.

A more responsible series might have shown what the ‘other’ side was doing. Thus, we get to hear of the assassination attempt on Lenin in 1918 (read off from a ticker tape). But we only get to see the execution of would-be murderer Fanny Kaplan and gruesome disposal of her body. No context is provided. More generally, we only find out indirectly how soon the Bolshevik regime was threatened by ‘White’ counter-revolutionaries and the Czech Legion in Siberia. As far as I can recall, no mention is made of the 10 countries that sent troops against the Bolsheviks, including Britain. These efforts were accompanied by various plots supported by foreign agents such as Bruce Lockhart.

The Bolsheviks did indeed resort to severe repression but they understandably felt they were literally fighting for their lives (Another Bolshevik leader, Uritsky, was killed at the same time as Lenin was badly wounded). This does not excuse Bolshevik and it is true that abuses by the Cheka started very early, with a number of brutes being ranked to its ranks (a flavour of which Sreda does capture). But a one-dimensional picture of the Bolsheviks as but bloodthirsty tyrants is not justified by the facts.[x]

Overall, Trotsky is squarely blamed for sowing the seeds of the subsequent show trials, mass executions and labour camps. He is the one who demands full-scale ‘red terror’ of “biblical proportions”, including concentration camps. He is the one who sets up the first show trial (Admiral Schastny). In the interviews, ‘Jacson’ repeatedly returns to the accusation that Trotsky started what Stalin only finished. To be sure, Trotsky was no saint. Critics such as Victor Serge rightly called him to account, for instance, over the repression of the Kronstadt rebellion (about which Trotsky spread a few cartloads of fake news).[xi]

In a final twist of the knife, this monster also has an Achilles heel. He is prone to hallucinations. He is that other old trope, the tormented soul. This narrative device is but a means to underline what a rotten beast he was. In this TV show trial, he is thereby found guilty twice over. At these moments he can be shown cringing in terror but he is still not permitted any signs of real humanity.

As in common in gangster movies, Sreda’s arch villain is shown to have the odd pang of remorse for his past crimes. Yet Trotsky’s final words, for instance, do not sound like those of a man regretting his life’s work.[xii] One might think that the Fourth International he launched was a ludicrous venture. One might doubt the merits of the ‘Transitional Programme’ it produced. One could question Trotsky’s vision of a better world[xiii] or his thoughts on ‘means’ and ‘ends’.[xiv] Yet it is hard to deny that he clearly stuck to his worldview right to the end.

Sreda makes but two concessions to the extremely one-sided portrayal. First, perhaps just following an old war movie trope, Trotsky is shown bravely rallying Red Army troops as they flee the field. Second, in the affair of what became known as the “philosopher’s steamboat”,[xv] Trotsky engineers the exile of intellectuals who were threatened with execution by the secret police. But Sreda does not concede too much. Trotsky’s action is portrayed as a means of placating his son Sergei rather than an act of genuine clemency. He is also more worried the practical impact on foreign opinion than by any real commitment to the principles of free speech.

There is a more positive picture of Trotsky when the series arrives at the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. In the negotiations with the Germans, Trotsky, as the Soviet commissar for foreign affairs was between a rock and hard place. Bolshevik delegates there before him (Joffre etc) had apparently been loose-lipped about Moscow’s weaknesses, sometimes after too much drink, and, as Sreda shows, Trotsky took firm control.

His position was not dissimilar to that of the IRA’s Michael Collins in the negotiations with Britain for Irish independence a bit later.[xvi] Collin’s fellow leaders were similarly divided on what to do as were Trotsky’s. On the one side, Lenin recognised the desperate need for peace (not well conveyed) while, on the other, several other Bolshevik leaders such as Bukharin called for revolutionary war (sort of shown). Trotsky was somewhat stuck in the middle, calling for neither war nor peace but hoping, perhaps naively, that a successful revolution in Germany would save the day. It did not happen and, after further advances by the German army, there was no alternative but to buy some time by giving away a crippling amount of land. Trotsky, as is shown, had probably made the best of a thankless job. The ‘haughtiness’ mentioned above could, of course, been a ploy to disguise his fundamentally weak position.

Sreda at least recognises that Trotsky was right on the issue of foreign food aid to relieve famine conditions in 1921-22. He is shown to be opposed by Stalin in particular. The latter seemingly would rather have seen many more thousands starve to death than be indebted to foreign generosity. The issue was not a simple one however. Food aid has often come tied with strings though in case American food does seem to have stopped a lot of people from starving.[xvii]

Overall, for Sreda, this is a man with, otherwise, few redeeming features. Trotsky’s towering intellect and skills as a thinker, writer and polemicist are simply ignored. Trotsky’s writings on literature, including his critique of the ‘Proletkult’, reveal a perceptive mind. It was also a prescient one that quickly spotted what a horrendous danger Hitler posed.[xviii]Furthermore, there is little doubt that he played the part of a leader during the Civil War without whom the Bolshevik regime would have really struggled to survive.[xix] Sreda’s picture of Trotsky-as-monster makes it hard to imagine why Trotsky managed to inspire genuine loyalty, not least after he fell from power and became such a vulnerable and politically isolated figure.

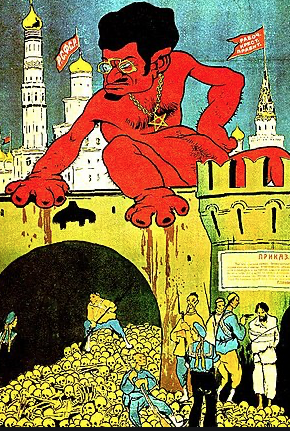

(as with the image above, this is an anti-Bolshevik poster of the time,

featuring the Jewish Trotsky as an orgre)

One Man Revolution

One of the most risible sequences of the whole series concerns the October Revolution itself. Trotsky is portrayed as some sort of Mephistopheles conjuring up the political takeover. For a good part of this section, he is shown alone in a room full of maps on which he plots the seizure of key buildings. Soldiers and sailors flood out at his command. Through Trotsky was indeed centrally involved in planning the move against the Provisional government, he was nonetheless only part of a group in and around the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee. It in turn was only one of several such bodies across Russia.

We only see two others, Kamenev and Zinoviev, the latter depicted as bumbling and weak, an image presumably to shore up that being built of the decisive and energetic Trotsky. In reality there was a fierce debate inside the Bolshevik Party about the seizure of power. Kamenev and Zinoviev in particular strongly opposed the plans. The party in 1917 was not the ‘machine’ it became in later years. [Stalin’s role would appear to have been fairly marginal during the final days].

What is utterly absurd is the portrayal of Lenin. He turns up very late to the ‘ball’ and is shown to be somewhat miffed by what Trotsky has gone and done in what is portrayed as his absence. Yet, if the Revolution had a mastermind and driving force, it was Lenin above all others, including Trotsky (who overtly recognised that reality in his writings on the subject). There can be little doubt that from the early days, Lenin has exercised a dominant influence on Bolshevik thinking.

‘Trotsky’ is of course about Trotsky but more effort could perhaps have been made to give more credit not just to Lenin but to several other influential figures such as Bukharin who were far from being mere ‘yes men’. The Marxist thinker Plekhanov does make an early appearance but his debate with Trotsky is somewhat reduced to one of grumpy old man versus jumped-up peacock.

Indeed, Lenin’s role rather contradicts the tenets of Marxist ‘historical materialism’ given that one individual was so central to what unfolded. Marxist historiography, including Trotsky’s own significant contribution, is similarly contradicted by the extent of contingency in the events. From far Sreda’s picture of them happening with almost clockwork precision, thanks to Trotsky, things could easily have gone the other way during, as well as before and after, October. History can suddenly shift in other directions for all sorts of reasons, some quite trivial and quite removed from the interaction of big forces and leading figures. There seldom is any ‘inevitability’ [xx]

More monsters

Trotsky is far from the only victim of fabrications and half-truths. There is, for example, Alexander Parvus (Helphand). He is another faker, one solely interested in making money. He seeks to ferment political breakdown in Russia for the benefit of his German paymasters and perceives Trotsky to be his tool. Here, the series revives the quite discredited theory that the German cash was behind the Russian revolution. Viewers would never guess that, for many years, Parvus was widely admired as a talented Marxist theoretician. It is true that he did descend into shady business dealings but this seems to have followed disillusionment after the failure of the 1905 Revolution.[xxi]

The role of this warped representation of Parvus in the narrative is actually quite poisonous. It goes way beyond just taking liberties with history. Here, we have a very shady rich Jew attempting to manipulate events in another country for perverse ends. This representation fits very conveniently with the anti-Semitism of regimes such as Vladimir Putin in Russia and Victor Orban in Hungary (remember the conspiracy theories circulated about George Soros).

In light of the above, the reader will perhaps not be surprised to learn that Lenin is portrayed as another wicked brute, solely interested in personal power. At one point, he even threatens to throw Trotsky off a roof, one of several make-belief events in this fiction. Lenin was certainly ruthless and single-minded, arguably to an unhealthy extreme. Yet, in reality, here again was a far more rounded character. Like Oliver Cromwell, he had his ‘warts’ but they were not his whole face. Where Sreda is on stronger ground in its depiction of Lenin’s final struggle and especially his fears about Stalin.[xxii]

Stalin is shown to be a violently jealous schemer. Early in the series he is depicted as a ruthless killer, murdering helpless guards during a hold-up. His hatred of Trotsky, we are told, stemmed from a small slight when, at an early party congress, Trotsky did not notice him and failed to shake his hand. Thereafter, Stalin lurks in the background, waiting his chance. Often, he is shown lurking behind Lenin, something that rather exaggerates the role he was playing in the party at the time.

In this crude caricature, the series misses part of the picture. Stalin certainly was an extremely violent and paranoid tyrant but Sreda’s series fails to show how deftly he manoeuvred to establish his rule.[xxiii] Dull-witted, he wasn’t: Trotsky was wrong to dismiss Stalin as an “outstanding mediocrity”. Stalin was, in fact, a serious student of Marxism and his theoretical work, its turgid prose notwithstanding, was closer to the Marxist canon (though perhaps more Engels than Marx) than many Marxists care to recognise. More importantly, his notion of ‘socialism in one country’ had genuine appeal in a war-ravaged country, whereas Trotsky’s advocacy of international revolution seemed only to offer more conflict. Unlike Hitler, Stalin was smart enough to back battle-winning generals such as Zhukov.

The series does actually mention what really tipped things in Stalin’s favour. Through the mouth of Trotsky himself, it is made clear that Stalin’s rise to power depended on a new social base, that of the fast multiplying number of party apparatchiks. Many owed a direct personal debt to Stalin for their appointments and promotions in the expanding bureaucracy.[xxiv] This new elite quickly began to get a sense of its own self-interest, one very different to that of the mass of workers and peasants. Putin’s power today stands on the descendants of that layer (plus some old-fashioned mobsters). It is rather convenient to dump all the blame for the crimes of Communism on Trotsky rather than Stalin, the real ‘gravedigger’ of the Revolution.

Loose women and lost masses

The Bolshevik Party actually had in its ranks an unusual number of highly talented individuals. A perhaps surprising number were women (though the party leadership was male dominated).[xxv] One of long-term activists was actually Natalia Sedova, Trotsky’s second wife. Not only was she an experienced political activist, she was also a clear-headed writer. Her resignation letter from the Fourth International, for example, provides a very cogent analysis of the Soviet system.[xxvi] Indeed, it is better than Trotsky’s convoluted attempts to maintain that Russia was still some sort of workers’ state, no matter how degenerated.

Not that such a history does her any good in Sreda’s reworking of history. In it, she is transformed first into a self-indulgent and somewhat frivolous lady of the salons before she falls (or, rather, is clutched) into Trotsky’s embrace. Afterwards, she quickly becomes more of a doormat. She is not alone in being smitten by Trotsky (frequently shown clad in tight black leather). The other main female characters cannot wait to (literally) jump on top of him. Thus Larissa Reisner, radical journalist and later officer in the Volga River flotilla in 1918, is depicted as nothing more than a voracious vamp. Then there is the artist Freda Kahlo. Her fling with Trotsky would appear, in Sreda’s picture, to have cured her of assorted physical ailments from which she suffered.[xxvii]

As might now be expected, Trotsky also acts as a vile cad by abandoning his first wife. In reality, it was Aleksandra Sokolovskaya who first politically educated Trotsky. Later, she agreed both to his flight and to subsequent divorce, seemingly remaining friends.[xxviii] According to Sreda, a rather naïve and ‘wet’ Trotsky received his political education instead from a prison governor, whose name he duly took, an assertion contradicted by Isaac Deutscher in his famous trilogy on Trotsky.

But at least one sees these women. The Bolshevik seizure of power depended greatly on the strong base they build in the big factories, especially in Moscow and St Petersburg. Though Russia was agrarian society with a peasant population dominant in numerical terms, it was also home to some modern factories in the cities. Soviets based on them were a critical institutional ingredient in the overthrow of Tsarism.[xxix] Some workers actually became leading figures in the party. But this critical social layer is conspicuous for its absence. Instead, Bolshevik muscle is shown to depend largely on a few sailors.

To be sure, the Kronstadt garrison in particular did play a significant role but the struggle to win support in the factories was more important.[xxx] The ‘July Days’ seem to have had their roots there, whereas, according to Sreda, these events are more a matter of violent looting by a handful of hooligan sailors (who, at a time of serious food shortages, simply throw food onto the ground rather than eat it or carry it away).

There is another group that puts in an appearance: liberal intellectuals. Sreda uses the real-life crackdown on the intelligentsia (eg shots of the Cheka breaking up university lectures and arresting professors) to demonstrate what, it is saying, was the inherently repressive nature of Bolshevism. Trotsky and his fellow leaders had talked about freedom but quickly acted to silence critical dissent. Sreda uses the figure of Maxim Gorky. It is certainly true that at the time the writer was very critical of the Bolsheviks “Lenin and his associates consider it possible to commit all kinds of crimes … the abolition of free speech and senseless arrests., he wrote.[xxxi]

What is especially revealing about this section of ‘Trotsky’ is the other intellectual Sreda chooses to use to present its story. He is Ivan Ilyin, a religious and political philosopher.. It might be useful to remember then that Ilyin was an apologist for fascism. Before, Ilyin had supported Russia’s disastrous involvement in World War One. He was no liberal intellectual in the western sense.[xxxii] Vladimir Putin is a great fan (he brought Ilyn’s bones back to ‘Mother’ Russia for burial), something that the Sreda team presumably understood.

The overheads of revolution

The Sreda series repeats the old trope that “revolutions devour their own children” (in the screenplay the words, or something like them, are put in the mouth of Trotsky’s father). It is true that, in the struggles such as the 1640 revolt against Charles 1 in England, the 1789 revolution in France and, of course, the 1917 Revolution in Russia, many members of the first wave of the revolution were subsequently killed by those who came to power next. Yet the same could be said of many types of regime, including long-established monarchies and empires. Kings killed princes and vice versa, while murderous purges by new powers-that-be routinely exiled, imprisoned or executed previous state ministers.

The trope is a lazy one since it obviates the need for serious analysis of specific times and places, teasing out what often were quite distinct factors at work. Instead, everything is put down to the workings of some universal rule. In the case of Russia, it leaves out pressures such as the impact of the World War One and then the ruinous Civil War as well as the role of foreign powers attempting to strangle the new regimes. There were specific difficulties too in the near impossible task of reconciling the demands of the cities and those of the countryside.

Such pressures fed into violent schisms which tore apart the Bolshevik Party. The Trotsky-Stalin split was not some iron law of history but a real conflict over the future of the regime. To be fair, matters were made worse by factors in Bolshevik ‘iron discipline’ and its ideology, not least a tendency to see life in abstract and crude categories (this or that class as if they were homogenous blocs, only capable of behaving one way).[xxxiii] It was compounded by a cavalier attitude towards individual human rights (‘bourgeois’ ideology). Thus, it was a terribly short step from talk of liquidating ‘Kulaks’ as a class to actual liquidation of individuals and families deemed to belong to that class (often they didn’t but that did not save them).

Any fanatical determination to create ‘utopia’ can indeed legitimise a lot of cruelty and destruction en route, with opponents and, soon, even those displaying what is deemed to be insufficient enthusiasm to be ground under. As John Gray argues,[xxxiv] dreams of total and immediate transformation of society, of a millennialist sweeping away, lock, stock and barrel, of the old order, and of ‘perfecting’ people can turn into all too real and all too terrible nightmares for actual people.Bolshevism did have such strands (as, today, does Islamic Fundamentalism).

More generally it can be argued that there was a strong strain of intolerance and a predilection for repressive measures in the Bolshevik worldview. Indeed, the young Trotsky had prophetically warned of the dangers in Lenin’s concept of party organisation of a “substitutionism” in which democratic norms are replaced by ever more centralised and top-down decision-making by a ruling clique and, ultimately, a sole dictator. Other radical socialists of the time such as Rosa Luxemburg also critiqued both Bolshevik theory and subsequent practice once in power.

Trotskyists were to talk a great deal and approvingly of “Leninist norms” but abuses grew in number when Lenin was in power and were not just confined to excesses by the Cheka. The revolution ‘degenerated’ well before the rise of Stalin. The first forced-labour camps were set up in 1918 and by 1921 the Gulag system had over 80 camps. Sreda spotlights the corruption in food distribution, for example. It is paralleled by a scene in the film adaptation of ‘Dr Zhivago’ in which the allocation of accommodation become controlled by petty and vindictive tyrants. The sympathetic American journalist John Reed soon become disillusioned with the new regime as did other visitors.[xxxv] It might be noted that once some of the more dogmatic policies of ‘War Communism’ were replaced by the new Economic Policy, food began to flow into the cities again: requisitioning had been a disaster.

But there remains a need to look at how things worked out in practice rather than rely on rather tired adages. As the former anarchist Victor Serge noted, the Bolshevik Party did contain germs but so too do all bodies. The question is rather what encourages those germs. The state of collapse across the Russian economy in the aftermath of World War One and then the Civil War was surely a major factor. The Sreda screenplay fails to tease out just how dependent were Bolshevik plans on the successful revolution in richer pats of Europe, thereby releasing aid with which to address Russia’s economic woes. It might be noted in passing that, according to the BBC website, the very first concentration camp in the young Soviet Russia was actually created by British and French interventionist forces on Mudyug Island near Arkhangelst for Boslshevik prisoners..

Dramatising versus falsifying history

Entertainment movies and TV dramas are of course not academic history tomes. Even TV documentaries are going to cut corners if only to fit into TV schedule running times. They often rely on reconstructions since actual footage is often not available (that too might give a distorted view).[xxxvi] Historical dramas on the big and small screen will cheery pick the best bits about their subject, amalgamate discrete events and characters as well as invent dialogue, especially if no-one knows what actually was said. Simplification is often necessary to make what happened comprehensible to audiences not familiar with a topic. Similarly, there will always be a tendency to focus on individual events rather than long-term background processes since these are easier to convey.

Sreda could claim, then, that it was simply offering an entertainment for modern audiences, far removed from the events of the early 20th century. Yet there are plenty of film and TV dramas that still give a reasonably accurate picture of what happened and why, whilst keeping their views entertained. Examples range from ‘Band of Brothers’ to ‘Chernobyl’, from ‘1864’ to ‘The Crown’, and from ‘Apollo 13’ to ‘All the President’s Men’.

There may be some really dramatic licence, for example, in Eisenstein’s ‘October’ (eg the staging of the storming of the Winter Palace)[xxxvii] but, at least, he got right the fact that, quite contrary to Sreda, it was Lenin, not Trotsky, who led the Bolshevik seizure of power. Then there is Warren Beatty’s ‘Reds’ which covers the central period of the timeline of ‘Trotsky’ only much better.[xxxviii] The satirical black comedy film ‘The Death of Stalin’ clearly took some historical liberties yet it still provided a real flavour of the murderous political machinations of that era. The BBC has shown that it is possible to stage a drama-documentary on 1917 that shows different viewpoints about the events.[xxxix]

Dramatic representations of history are, then, inherently problematic.[xl] Facts regularly get mixed in with pure imagination. What is not acceptable, however, is the wholesale distortion of history and, in this case, the strong smell of anti-Semitism. I do not know what the relationship is between Sreda and the Putin regimes. Perhaps the form the production of ‘Trotsky’ took was just a matter of keeping in with the authorities. Whatever the relationship, there is no disguising the fact that ‘Trotsky’ is not about giving a reasonably accurate but still entertaining representation of its subject’s life and times. It serves up too many fabrications, somewhat echoing Stalin’s own lie machine, all, in effect if not intention, serving to legitimise the brutal and repressive regime now in power in Moscow.

Apart from the boost given to anti-Semitism, Sreda is saying in effect that all struggle to improve society is pointless and indeed counter-productive: you might as well put up with what you’ve got. Putin is a creature of the machine inherited from the Stalinist years. Sreda plays safe: blame Trotsky for all that has gone wrong in Russia. But it also serves the myth-making of the new ruling caste. Indirectly ‘Trotsky’ endorses the notion that the current regime is a break from the (bad) past and can offer a (good) future of a ‘true’ Russia reborn. Critics of Putin and his clique are, then, just like Trotsky and Parvus presented by Sreda: agents of foreign interests.

In sum, ‘Trotsky’ is a concoction truly fit only for the dustbin of media history. It might not be right to censor it but Netflix could have commissioned a documentary to give viewers a better view of what really happened. As it stands, Netflix is just being a channel for toxic propaganda that could have come from the Kremlin.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

[i] As I type, I have on a bookshelf near me a somewhat worn copy of ‘Memoirs of a Revolutionary’ by Victor Serge, a book I chose when I won a school prize for A Level results back in 1968.

[ii] https://www.rbth.com/history/330040-why-did-trotsky-execute-hero

[iii] Compare with this eye witness account: https://www.marxists.org/subject/women/authors/reissner/works/svyazhsk.htm?fbclid=IwAR1BzTnsNJUPBZpxYdWOA6IX1kuYhixVn6_G2gwDKdnfvuh7OhlvPCAiKAM

[iv] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/sep/13/trotsky-ice-axe-murder-mexico-city For better coverage of Trotsky’s final period, see: https://www.harpercollins.com/9780061938436/trotsky/

[v] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/nov/03/russian-revolutions-rocknroll-star-trotsky-gets-centenary-tv-series

[vi] If we follow the logic of Sreda’s representation, this article might have been written by someone else not Trotsky: https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/document/obits/sedobit.htm

[vii] https://www.peterlang.com/view/9783631695548/xhtml/chapter003.xhtml

[viii] Paragraph 23 here: https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1930/mylife/ch24.htm

[ix] https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/ni/vol02/no01/lenin.htm

[x] It is worth comparing Sreda’s picture with the descriptions in, for example: https://www.faber.co.uk/9780571269068-six-weeks-in-russia-1919.html ; https://www.haymarketbooks.org/books/943-lenin-s-moscow ; https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/211691/memoirs-of-a-revolutionary-by-victor-serge-translated-by-peter-sedgwick-foreword-by-adam-hochschild/ ; https://archive.org/details/whatisawinrussi00lansgoog/page/n70

[xi] https://www.marxists.org/archive/mett/1938/kronstadt.htm

[xii] See: https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/fi-is/no7/testaments.htm

[xiii] For a critique from a ‘green’ perspective, try: http://www.trotskyana.net/GuestContributions/irvine_prophet.pdf

[xiv] Three examples; https://socialistregister.com/index.php/srv/article/view/5565 , https://www.marxists.org/archive/shachtma/1961/xx/terrcomm.htmland https://www.marxists.org/archive/serge/1940/trotsky-morals.htm

[xv] https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/08/books/08grim.html

[xvi] The eponymous movie takes some liberties with history but, unlike ‘Trotsky’, still manages a far fairer picture of its subject’s life and times, whilst not sacrificing entertainment value.

[xvii] https://www.hoover.org/research/food-weapon

[xviii] https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/themilitant/1945/v09n19/trotsky.html

[xix] It did have the advantages of ‘interior lines’ and opponents who were badly divided and, fatally, who failed to coordinate their efforts. Yet the fledgling regime faced enormous odds which Trotsky certainly managed to shorten.

[xx] https://profilebooks.com/historically-inevitable.html

[xxi] https://spartacus-educational.com/Alexander_Parvus.htm

[xxii] https://www.press.umich.edu/93113/lenins_last_struggle

[xxiii] https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/299269/stalin-by-stephen-kotkin/

[xxiv] Some socialists at the time concluded that a new kind of society, a ‘bureaucratic collectivism’, was emerging eg https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/10492079-neither-capitalism-nor-socialism Another group saw the Soviet Union as ‘state capitalist’ eg https://www.marxists.org/archive/cliff/works/1964/russia/index.htm

[xxv] 18 of the 21 members of Central Committee at the time of the revolution being men, for example

[xxvi] https://www.marxists.org/archive/sedova-natalia/1951/05/09.htm

[xxvii] https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-frida-kahlos-love-affair-communist-revolutionary-impacted-art

[xxviii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aleksandra_Sokolovskaya

[xxix] https://spartacus-educational.com/RUSsoviet.htm

[xxx] See: https://www.plutobooks.com/9780745399980/the-bolsheviks-come-to-power-new-edition/ See also: http://web.mit.edu/russia1917/papers/1024-WorkerSupportfortheBolshevik%27sOctoberRevolution.pdf

[xxxi] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maxim_Gorky#cite_note-25

[xxxii] http://www.openculture.com/2018/06/an-introduction-to-ivan-ilyin.html and https://www.ridl.io/en/ivan-ilyin-a-fashionable-fascist/

[xxxiii] This study captures something of that unquestioning discipline: https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/546/54650/the-whisperers/9780141013510.html . The punitive nature of the Bolshevik mindset manifested itse;lf quite early on. See the work on Anne Applebaum, gor example. The best fictional portrayal remains: https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/111/1113694/darkness-at-noon/9781784875459.html

[xxxiv] https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/557/55721/black-mass/9780141025988.html

[xxxv] See the reports of the (anarchist) Emma Goldman, for example: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/goldman/works/1920s/disillusionment/ch04.htm On Reed: https://spartacus-educational.com/Jreed.htm

[xxxvi] War photography, for example, has had a long problematic history: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2002/12/09/looking-at-war

[xxxvii] https://www.rbth.com/history/326637-fall-of-winter-palace-how-1917

[xxxviii] https://www.theguardian.com/film/2012/may/02/reds-votes-left-warren-beatty

[xxxix] https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b098pgf1

[xl] Eg http://www.culturahistorica.es/rosenstone/historical_film.pdf

You must be logged in to post a comment.